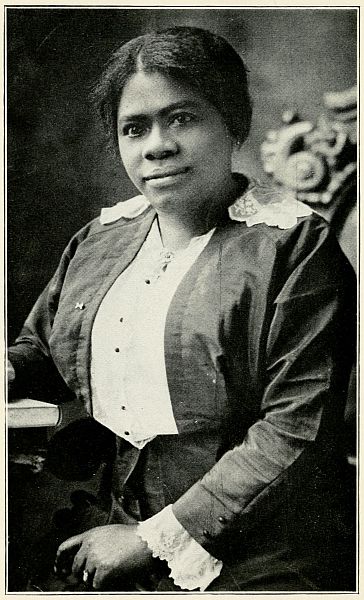

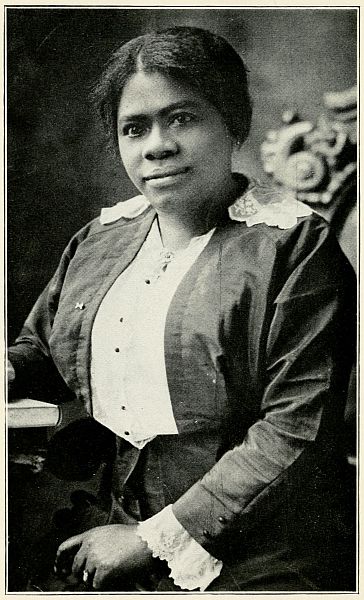

If we accept and acquiesce in the face of discrimination, we accept the responsibility ourselves. We should, therefore, protest openly everything ... that smacks of discrimination or slander.

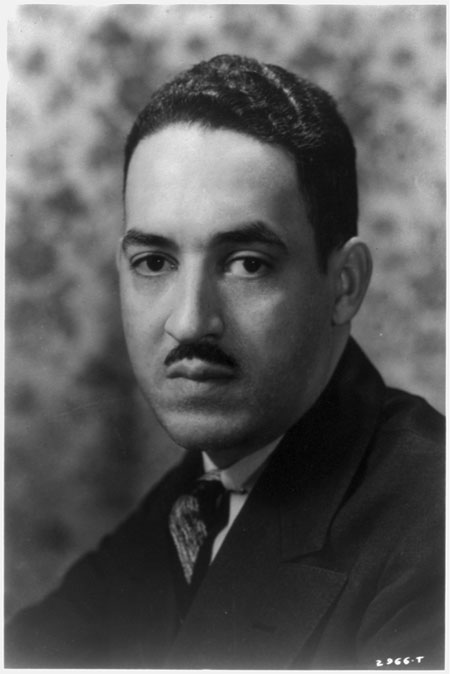

-Mary McLeod Bethune

A lot of people don't know but I attended Bethune Cookman College for a while. It was there I realized that I really DID want to serve in the United States Army and it was there I saw the evidence and result of Maya Angelou's "I Rise" poem. It was at BCC I began to feel pride in a people that went beyond those whom I knew personally and I began to cast away my own prejudices and discrimination against my own people (yes, I had them). It would take me a long time to deal with the self-hatred that I held within me because of the color of my skin that came about because of the racism that surrounded (and still surrounds) me on a daily basis in both blatant and subtle manners but it was at BCC that self-hatred began to crack and fall away. I want to honor the woman for whom the school was named on this third day of Black History Month.

****

Born near Mayesville, S.C. on July 10, 1875, on a rice and cotton farm, Mary Jane McLeod was the fifteenth of seventeen children, some of whom had been sold into enslavement. In order to do their best by their children, her parents sacrificed so they could buy land to farm. Mary had the same determination. From childhood on, she took advantage of opportunities that were presented to her. Her parents, who had been born into enslavement, wanted their children to have an education. When Mary was about eleven, the Mission Board of the Presbyterian Church opened a school for African-American children. It was about four miles from her home, and the children had to walk back and forth to school, but Mary wanted to go. Her mother commented that some of the children had to be forced to attend, but not Mary, who was well aware of her family's relative poverty. Mary saw education as the key to improving the lives of African-Americans. An incident that occurred when she was quite young may explain this. Mary picked up a book while she was playing with a white child whose parents employed Mary's mother. The white child grabbed the book and told Mary she couldn't have it because African-Americans couldn't read. For Mary, education became the answer to the question, how can African-Americans move up the ladder in American society?

Invest in the human soul. Who knows, it might be a diamond in the rough.

Mary McLeod Bethune

A few years later, Mary had the chance to further her education when a woman in Detroit offered to pay for the expenses of one child at Scotia Seminary in North Carolina. Mary was selected by her teacher because she was an excellent student. After attending Scotia Seminary, she received a scholarship to the Moody Bible Institute in Chicago, where she continued to be a high achiever. Mary was the only African-American student there, and one of only a few non-whites.

As a child of twelve, Mary had been inspired by the words of a preacher who spoke of the need for missionaries in Africa. Mary completed the two year program, planning to go to Africa as a missionary, but was told that there were no open positions available at that time for African-Americans. Although disappointed, she returned to Mayesville and taught there for a year at the mission school she had once attended before requesting a new position from the Presbyterian Board of Education. She accepted a position as a teacher in Augusta, Georgia at Haines Institute, where she worked under the educator Lucy Laney. She gained a reputation as an "enthusiastic" teacher who held "Mission School" classes for children gathered off the streets on Sunday afternoons. She taught there for a year.

The whole world opened to me when I learned to read.

Mary McLeod Bethune

Mary was sent next to Sumter, S.C. where she taught for two years at Kendall Institute before marrying Albertus Bethune in 1898. The couple moved to Savannah, Georgia, where Albertus had a new job. Mary did a little social work, but mainly she concentrated on raising her son, Albert, who was born in 1899. The marriage was not a success, although the couple remained together until 1907 and on good terms thereafter. Mary was restless, and she felt called to public service. A visiting minister from Palatka, Florida urged her to move there and manage the new mission school he was starting. So in 1899 she moved to Florida with her son, followed by her husband. In Palatka she taught at the Mission School and visited prisoners in the county jail, reading and singing to them. She tried to help the prisoners in any way she could, and worked to free those who were not guilty. Because money was tight, Mary supplemented the family income by selling life insurance.

The school grew, but Mary was not content. She wanted to provide opportunities for African-American girls, and to do this she would found a school. She hoped to build the school in a new area, and a minister suggested Daytona. Five years after arriving in Palatka, she moved to Daytona, Florida. Almost penniless, she was sheltered by a local woman recommended by the minister, who helped her find the house that she would use to open a school for African-American girls. This was her dream, and she worked to make it come true. The house was bare, and Bethune was forced to repair furniture and use discarded carpets. She went to local stores to beg for boxes, which she used for chairs, and packing crates, which became her desks. In October of 1904, she opened the Daytona Educational and Industrial Training School with a student body of five. Each child paid fifty cents a week in tuition. In line with beliefs of the day, Bethune's primary focus was on training girls to take care of the home, so cooking and sewing were offered as well as the three "r"s. Before long, she also had several boarders. Bethune worked hard to keep her little school going, baking sweet potato pies to sell, and soon involving the community in her efforts. The school was a success, despite its difficult beginning. Within three years Bethune was able to relocate it to a permanent facility. Over the years, the one small house was replaced by a thirty-two acre campus with fourteen buildings and 400 students. A farm was purchased with the goal of making the school more self-sufficient. In 1923 the school became coeducational when it merged with Cookman Institute of Jacksonville, Florida, and became Bethune-Cookman College. Her house on the campus is maintained as a National Historic Landmark.

I leave you love. I leave you hope. I leave you the challenge of developing confidence in one another. I leave you respect for the use of power. I leave you faith. I leave you racial dignity.

-Mary McLeod Bethune

Bethune understood the importance of political participation. In the early 1900s, the battle for women's suffrage was underway, but there was little role for African-American women, especially in the South. In 1912 Bethune joined the Equal Suffrage League, an offshoot of the National Association of Colored Women. In an era when even African-American men couldn't vote, a frustrated Mary had to sit back and watch as white-dominated organizations marched and protested nationwide. But in 1920, after passage of the 19th amendment, the time for action had come. Bethune believed that if African-American women were to vote, they could bring about change. Riding a bicycle she had used when she was raising money for her school, she went door to door raising money to pay the poll tax. Her night classes provided a means for African-Americans to learn to read well enough to pass the literacy test. Soon one hundred potential voters had qualified. The night before the election, eighty members of the KKK confronted Bethune, warning her against preparing African-Americans to vote. Bethune did not back down, and the men left without causing any harm. The following day, Bethune led a procession of one hundred African-Americans to the polls, all voting for the first time.

For I am my mother's daughter, and the drums of Africa still beat in my heart. They will not let me rest while there is a single Negro boy or girl without a chance to prove his worth.

-Mary McLeod Bethune

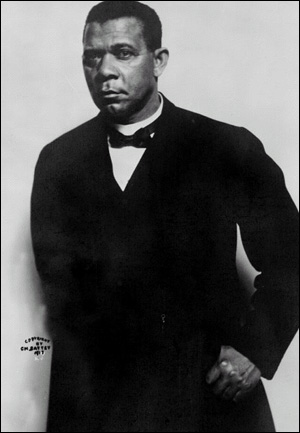

The story of her defiance of the Klan spread, and soon she was in demand as a speaker for the rights of African-Americans. Meeting many prominent people was in some ways an eye-opener for her. She met the African-American leader and scholar W.E.B. Dubois, and after hearing him comment that because of his race he couldn't even check out one of his own books from a southern library, she made her own school library available to the general public. This was the only free source of reading material for African-Americans in Florida at that time.

Bethune continued her career in public service as the years went by. She was elected to the National Urban League's Executive Board in 1920, the only Southern woman of any race. She helped to establish a home for delinquent African-American girls, she was president of the Southeastern Federation of Women's Clubs, and she was elected as president of the 200,000 member National Association of Colored Women twice in the 1920s. She used her position in the latter organization to speak out in favor of education for African-Americans, making speeches. She also served as president of the National Association of Teachers in Colored Schools and on the Interracial Council of America. She was a founder and the first president of the National Council of Negro Women in the 1930s. In 1932 Bethune was featured in a newspaper story by a well-known journalist, Ida Tarbell, as one of the fifty greatest American women. She was number ten on the list.

If we have the courage and tenacity of our forebears, who stood firmly like a rock against the lash of slavery, we shall find a way to do for our day what they did for theirs.

-Mary McLeod Bethune

The quality of Bethune's work was recognized by national politicians as well. Presidents from Coolidge to Roosevelt appointed her to government positions. President Coolidge invited her to attend his Child Welfare Conference in 1928. President Hoover appointed her to the White House Conference on Child Health in 1930. Her experience in the education field and her knowledge of the state of African-American education made her a valuable asset to both Presidents. She was also President Roosevelt's Special Advisor on Minority Affairs from 1935 to 1944. Her home in Washington, D.C., the Council House, where she did much of her work, is maintained by the National Park Service.

From 1936 to 1944 she held the position of Director of the Division of Negro Affairs of the National Youth Administration, making her the first African-American woman to become a federal agency head. Black advisors had been appointed for each federal agency, and their power was minimal. Bethune, however, had an agenda. She wanted to see African-Americans fully integrated into American life. She gathered a group of prominent men at her apartment in Washington for the first of many informal discussions. Because she had access to the president, she was able to take the suggestions made by this group to him, and see more blacks appointed to advisory positions. Her group became the Federal Council on Negro Affairs, and became known as the "Black Cabinet". As a member and a leader of this group, Bethune served as an unofficial advisor to President Roosevelt.

After World War II, she was one of three African-American consultants to the U.S. delegation involved in developing the United Nations charter. Bethune served as the personal representative of President Truman at the inauguration ceremonies in Liberia in 1952.

Cease to be a drudge, seek to be an artist.

-Mary McLeod Bethune

Always opposed to segregation, Bethune networked with influential whites to gain more opportunities for blacks. She was first introduced to Eleanor Roosevelt at a luncheon held by Roosevelt's mother-in-law in the 1920s. The only African-American present, she had to face the horrified stares of several Southern white ladies who were present. Mrs. Roosevelt, senior, Bethune's hostess, led her into the dining room, seated her in the place of the guest of honor, and introduced her to her daughter-in-law, Eleanor.

As the years went by, the two younger women learned to know each other better. Bethune developed very close ties with First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt in the 1930s and 1940s. Bethune understood how to use the power structure. She spoke out vehemently when African-American women were not permitted to participate in the national advisory council of the War Department's Women's Interest Section in 1941, going public as well as complaining to the Secretary of War. She also worked behind the scenes with Mrs. Roosevelt, and eventually won that battle. Participation in the advisory council put her in a position to see that African-American women became officers in the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps established a year later.

Bethune was recognized for her hard work during her lifetime and received many honors. She was a recipient of the Spingarn Medal in 1935, the Frances Drexel Award for Distinguished Service in 1937, and the Thomas Jefferson Award for leadership in 1942. She received an honorary Doctor of Humanities degree from Rollins College in 1949, the first African-American to receive an honorary degree from a white southern college. She received the Medal of Honor and Merit from the Republic of Haiti in 1949 and the Star of Africa from the Republic of Liberia in 1952.After a lifetime of achievements, Mary Bethune died on May 18, 1955. On July 10, 1974, ninety-nine years to the day after Bethune's birth, she became the first woman and the first African-American to be honored with a statue in a public park in Washington, D.C. The statue, in Lincoln Park, is a reminder of her achievements. South Carolina has honored its native daughter as well, hanging her portrait in the state capitol in Columbia.

(*

http://www.usca.edu/aasc/bethune.htm*)

From the first, I made my learning, what little it was, useful every way I could.

-Mary McLeod Bethune

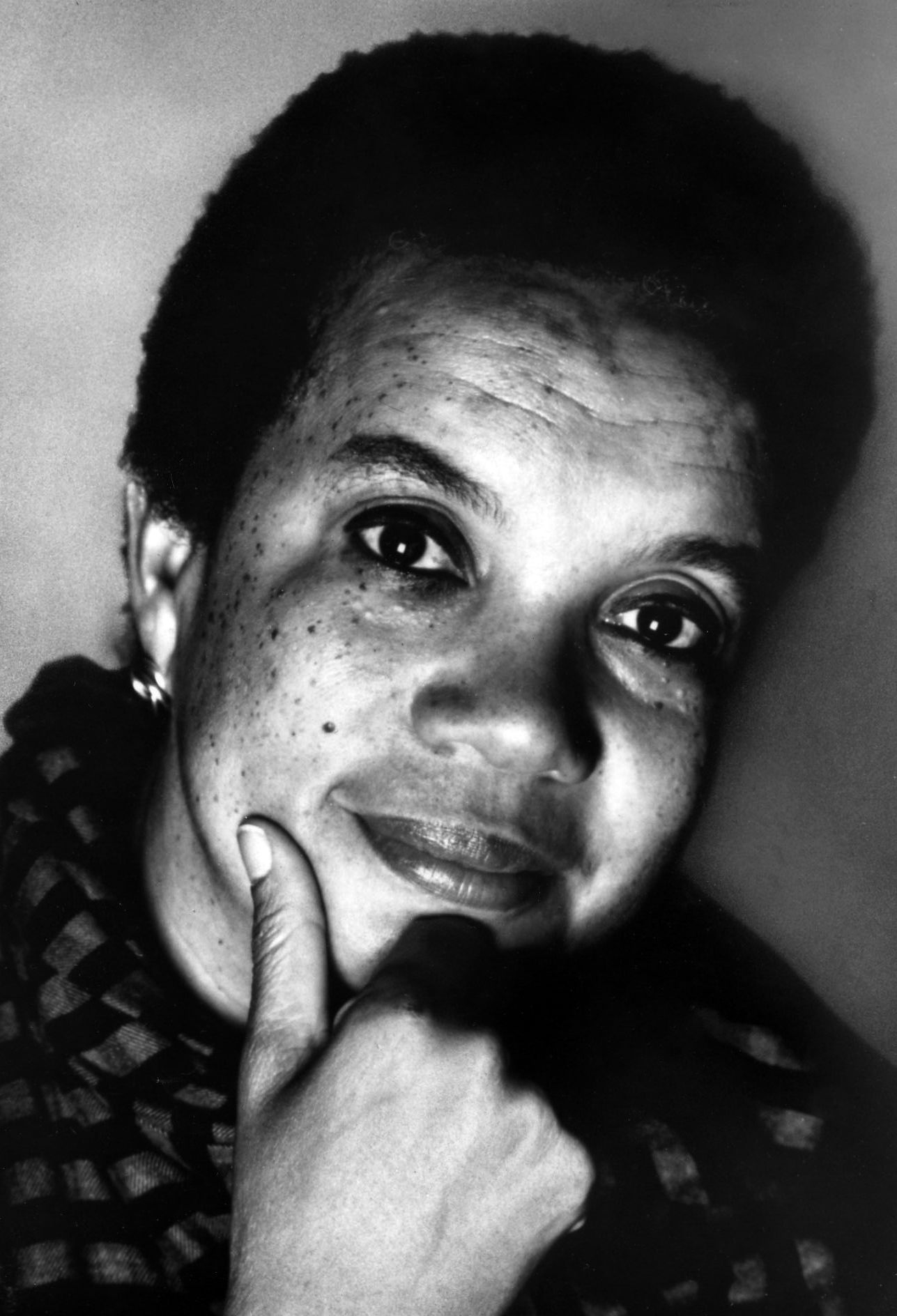

Marian Wright Edelman was born in 1939 in Bennetsville, South Carolina. She briefly attended Spelman College, then studied abroad on a Merrill scholarship, and eventually traveled to the Soviet Union on a Lisle fellowship. In 1959 she returned to the U.S., took an active role in the civil-rights movement, and graduated from Yale Law School in 1963, becoming the first African-American woman ever admitted to the Mississippi bar. Edelman launched her post-academic career by working on a voter-registration project targeting Mississippi blacks, and later found employment with the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. In 1968 she married civil-rights attorney Peter Edelman.

Marian Wright Edelman was born in 1939 in Bennetsville, South Carolina. She briefly attended Spelman College, then studied abroad on a Merrill scholarship, and eventually traveled to the Soviet Union on a Lisle fellowship. In 1959 she returned to the U.S., took an active role in the civil-rights movement, and graduated from Yale Law School in 1963, becoming the first African-American woman ever admitted to the Mississippi bar. Edelman launched her post-academic career by working on a voter-registration project targeting Mississippi blacks, and later found employment with the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. In 1968 she married civil-rights attorney Peter Edelman.