“I would like to be in a position where I can be of use to my race.” - Letter from Alexander Thomas Augusta to President Abraham Lincoln

What an inspiration Alexander Thomas Augusta was. He is a man of many "firsts" and when I found out about him a few years ago I found myself smiling because I could see much of Alexander Augusta in me (and not just because of the whole "Alexander" thing either). Besides of our connection to Virginia, we were both men who served our country in the United States Army. We both were born free, though in my case this was not something that is so amazing, in Mr. Augusta's case it was definitely something noteworthy. We both love to read and are driven toward our goals. We have both written to the president in our quest to make the world a better place for those whom we feel are being oppressed.

Alexander Thomas Augusta wanted to be in a position to be of use to his race. I do as well. But not just to the African-American people exclusively, but to the world as a whole.

Mr. Augusta's story is inspirational in that he refused to sit back and watch others be oppressed. Alexander was born free, he had more freedom and rights than other blacks. He could have lived his life without sparing them another thought. Without getting involved and contributing anything. He could have faded into the page of history without being a chapter heading at all, but he didn't want that to be his legacy. He didn't want that to be his impact upon the world. He refused to sit back and do nothing. He got involved and he made a difference. A BIG one.

Please join with me in honoring Alexander Thomas Augusta.

****

Augusta remained in Toronto, Canada West, establishing his medical practice. The City of Toronto placed him in charge of an industrial school. He supported local antislavery activities. He also founded the Provincial Association for the Education and Elevation of the Coloured People of Canada, a literary society that donated books and other school supplies to black children, as a way of giving back to the community. Augusta left Canada for the West Indies in about 1860, returning to Baltimore at the beginning of the American Civil War in 1861.

On February 1, 1864, Augusta wrote to Judge Advocate Captain C. W. Clippington about discrimination against African-American passengers on the streetcars (most likely horse-drawn) of Washington, D.C.:

Sir: I have the honor to report that I have been obstructed in getting to the court this morning by the conductor of car No. 32, of the Fourteenth Street line of the city railway.

I started from my lodgings to go to the hospital I formerly had charge of to get some notes of the case I was to give evidence in, and hailed the car at the corner of Fourteenth and I streets. It was stopped for me and when I attempted to enter the conductor pulled me back, and informed me that I must ride on the front with the driver as it was against the rules for colored persons to ride inside. I told him, I would not ride on the front, and he said I should not ride at all. He then ejected me from the platform, and at the same time gave orders to the driver to go on. I have therefore been compelled to walk the distance in the mud and rain, and have also been delayed in my attendance upon the court. I therefore most respectfully request that the offender may be arrested and brought to punishment.

His letter was printed in New York and Washington newspapers. On February 10, 1864, Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner introduced a resolution in Congress:

Resolved, That the Committee on the District of Columbia be directed to consider the expediency of further providing by law against the exclusion of colored persons from the equal enjoyment of all railroad privileges in the District of Columbia.

To support his resolution, Sumner read to the assemblage Dr. Augusta's letter.

Edward Bates, the Attorney General in President Abraham Lincoln's cabinet, belittled the incident and senators who supported Sumner.

Augusta wrote a letter of protest against the unfair treatment put upon African Americans who ride trains to Major General Lewis Wallace. That letter preceded Plessy vs Ferguson in attempting to eliminate racial segregation on transportation in the U.S. On March 13, 1865, he was brevetted to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel.

On February 26, 1868, Augusta testified before the United States congressional Committee on the District of Columbia with regard to Mrs. Kate Brown. Mrs. Brown, an employee of Congress, had been injured when an employee of the Alexandria, Washington, and Georgetown Railroad forcibly ejected her from a passenger car. The railroad was prohibited by its charter from discrimination against passenger because of race.

Augusta returned to private practice in Washington, D.C. He was attending surgeon to the Smallpox Hospital in Washington in 1870. He also served on the staff of the local Freedmen's Hospital and was placed in charge of the hospital in 1863, becoming the first black hospital administrator in U.S. history. Augusta taught anatomy in the recently organized medical department at Howard University from November 8, 1868, to July 1877, becoming the first African American appointed faculty of the school and also of any medical college in the U.S. He had received honorary degrees of M.D. in 1869 and A.M. in 1871 from Howard.

Despite his accomplishments, Dr Augusta was repeatedly refused entry to the local society of physicians, an affront that he feared would impede the progress of younger African-American physicians in the city. He died in Washington on December 21, 1890, interred with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery he is buried in Section 1, Lot 124A, map grid G/33.

Augusta's headstone reads as follows: "Commissioned surgeon of colored volunteers,April 4, 1863, with the rank ofMajor. Commissioned regimental surgeon ofthe 7th Regiment of US. Colored Troops, October 2, 1863. Brevet Lieutenant Colonel of Volunteers, March 13, 1865, forfaithful and meritorious services-mustered out October 13, 1866."

(*http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexander_Thomas_Augusta*)

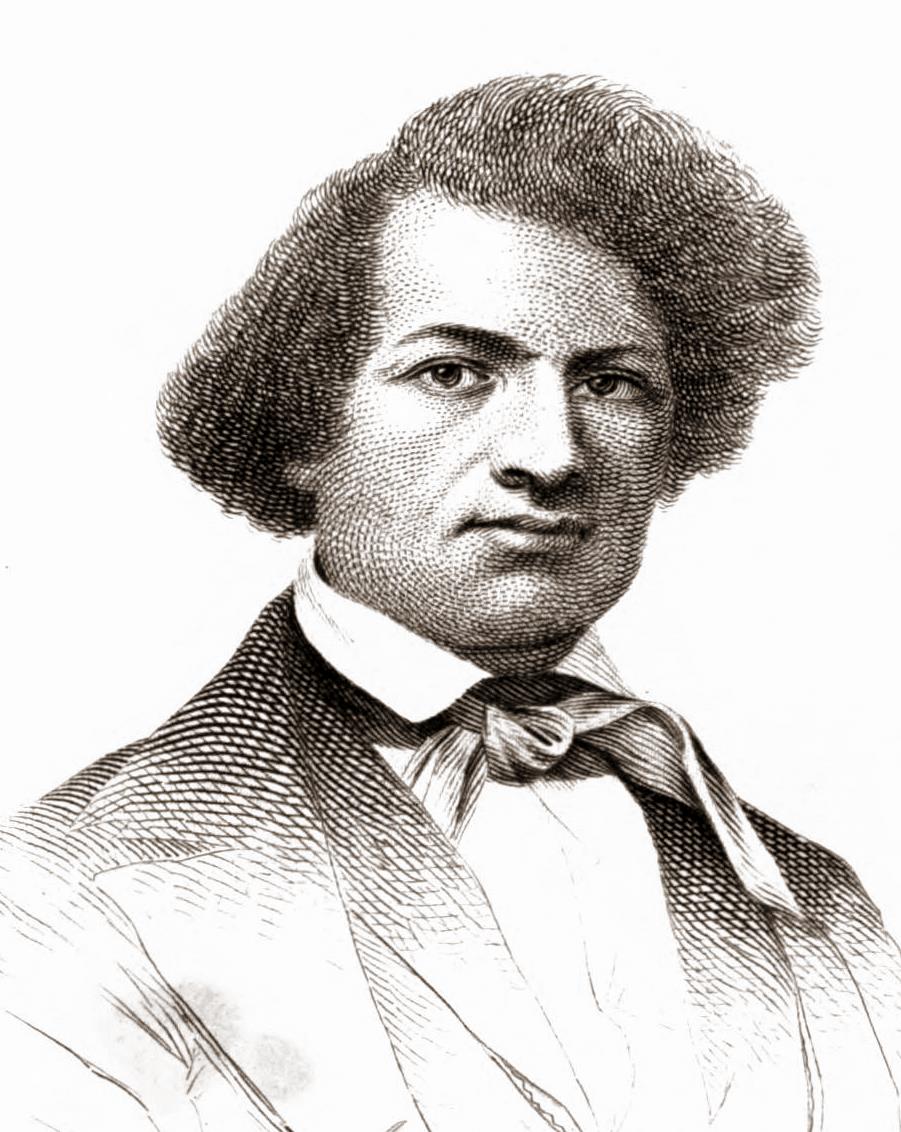

Determined to become a medical doctor, Alexander T. Augusta moved to various cities in search of employment to support his dream, finally graduating from medical school in Toronto. He distinguished himself in all of his appointments. He was the first black commissioned and the highest black officer in the segregated U.S. Army, serving with the U.S. Colored Troops. He headed the old Freedmen’s Hospital at Camp Barker, where he was the first black in the country to direct a hospital. One of the original faculty members of the nearly all-white Howard University Medical Department, Alexander Augusta became the first African American faculty member of any medical school.

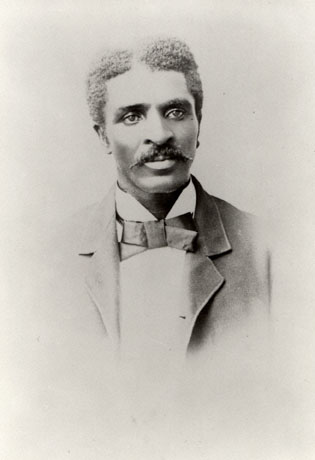

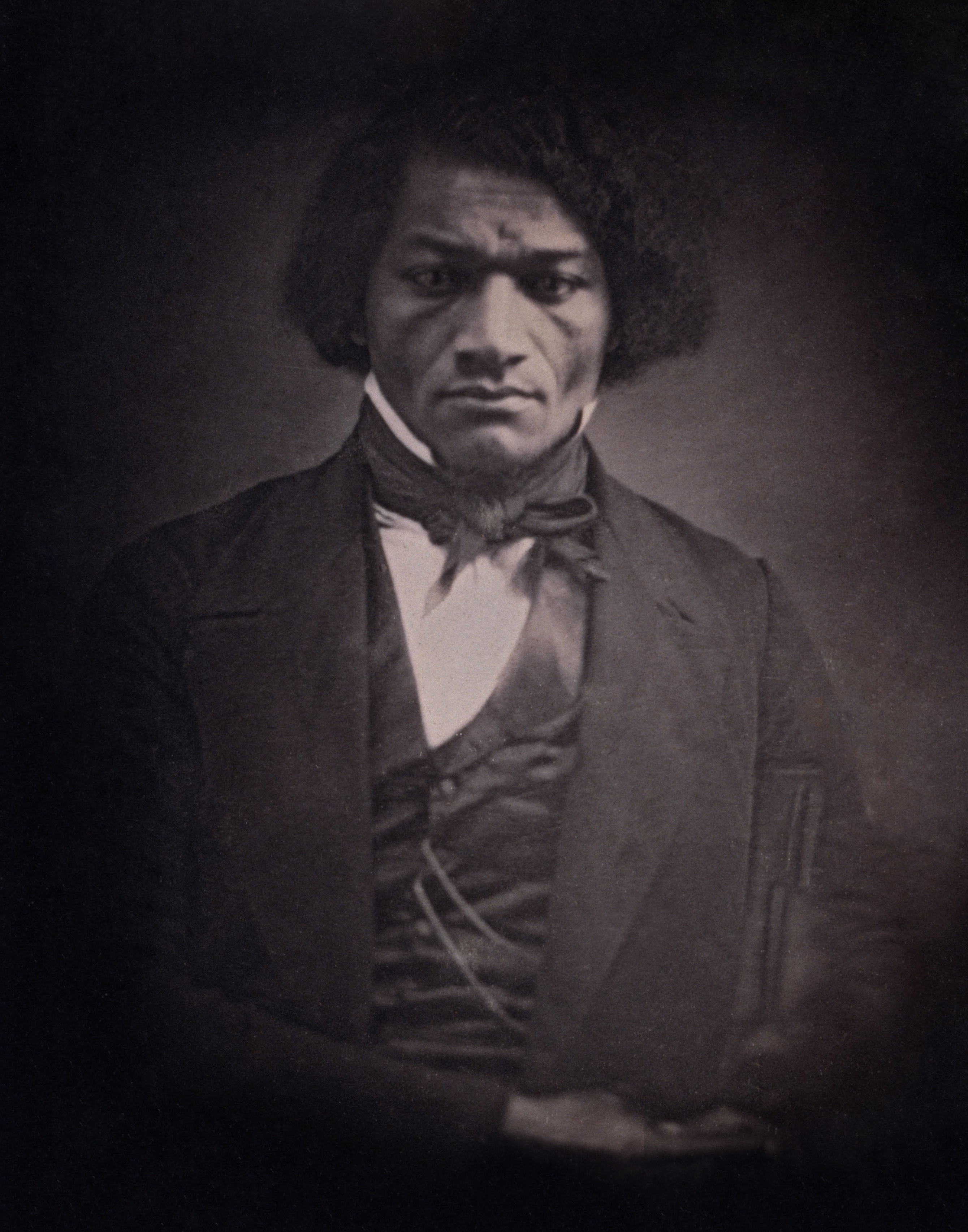

Alexander Thomas Augusta was born free in Norfolk, Virginia, on March 8, 1825. Although by Virginia law blacks were forbidden to read, Daniel Payne, later a bishop in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, taught Alexander the little reading that he knew early on. The young Augusta served as an apprentice with a local barber, where his reading was developed further, and then he moved to Baltimore where he worked as a journeyman barber. At the same time he studied medicine under private tutors. He relocated to Philadelphia, where he hoped to study medicine formally at the University of Pennsylvania’s medical school. His inadequate preparation led the school to refuse Augusta admission. Then William Gibson, a professor in the school, took an interest in him and arranged to have the young man study in his office. Augusta’s interest in formal medical study never waned.

Chronology

1825 Born in Norfolk, Virginia on March 8

1847 Marries Mary O. Burgoin

1856 Receives Bachelor of Medicine degree from University of Toronto

1863 Commissioned major in the U.S. Colored Troops, 7th U.S. Colored Infantry, U.S. Army; heads Freedmen’s Hospital, becoming first black to head a hospital

1865 Assigned to Department of the South; brevetted a lieutenant colonel, U.S. Volunteers, the first black to hold that rank

1866 Musters out of army; opens private practice in Washington, D.C.

1868 Becomes first black teacher at any medical school in the United States

1877 Reenters private practice

1890 Dies in Washington, D.C. on December 21

1896 Receives honorary degree of Medicinal Doctor from Howard University

Early Work in Toronto City Hospital

Augusta returned to Baltimore and on January 12, 1847, married Mary O. Burgoin, a woman of Huguenot descent, and the couple left for California. He worked in hopes of earning enough money to support his medical training but returned to Philadelphia three years later. A medical degree remained uppermost in his mind. Still later he moved to Canada, and in 1850 he was accepted into the Medical College of the University of Toronto. Six years later (1856), he received a B.M. degree from the university. The city took an immediate interest in him and acknowledged his expertise by placing him in charge of Toronto City Hospital and later in charge of an industrial school. In the meantime, Augusta set up private practice in Toronto. Sometime before 1860 he went to the West Indies and in 1861 returned to Baltimore and made a brief return to Toronto. Meanwhile, Augusta had become interested in the Union forces, the army’s volunteer medical service, and in October 1862 he sought a post in that service.

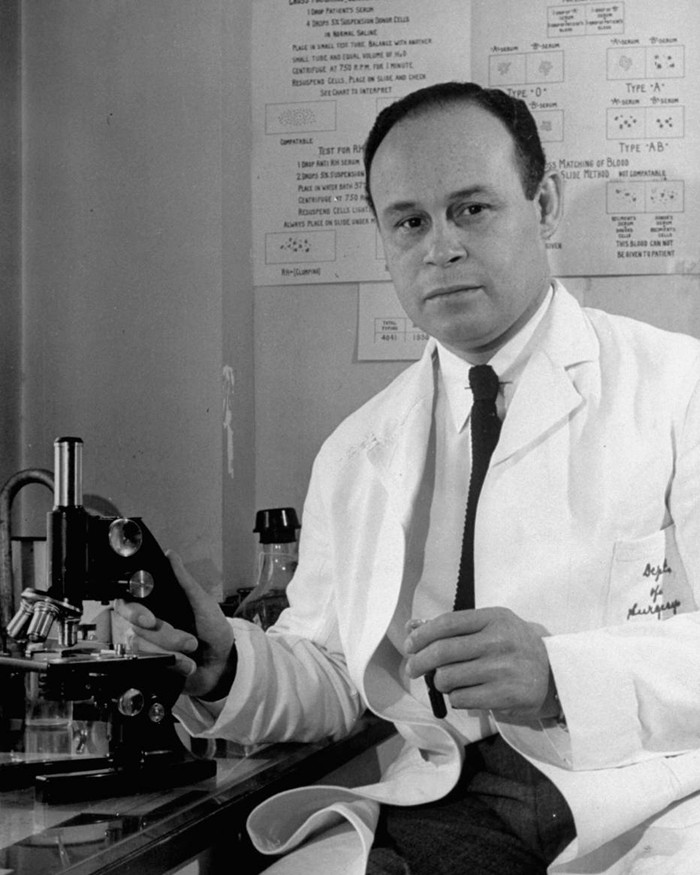

When he was given a medical commission and appointed surgeon of the U.S. Colored Troops, U.S. Army, on April 14, 1863, Augusta had the rank of major. He was the first of eight black physicians commissioned and the highest ranking black officer in the segregated U.S. Army. Augusta was sent to the 7th U.S. Colored Infantry and joined them in garrison at Camp Stanton, near Bryantown, Maryland. White officers, who were also surgeons, complained because they were subordinate to a black officer, causing him to be transferred to what became known as Freedmen’s Hospital, at the site of Camp Barker near Washington, D.C. There he became the first black to head any hospital in the United States. (This location was a different site from the Freedmen’s Hospital of later times.)

Racism in the U.S. Army

During the Civil War, thousands of escaped slaves settled in Washington, D.C, and lived in overcrowded, filthy quarters. Disease was rampant. Although the federal government built new hospitals and enlarged others, sick freedmen were treated at Camp Barker in the fall of 1863, where Alexander was in charge. The War Department continued to direct the hospital until 1865, when it came under the auspices of the newly created Freedmen’s Bureau. Later on, the Freedmen’s Hospital was established on a permanent basis and erected on the campus of Howard University. Alexander remained at Freedmen’s from autumn 1863 to spring 1864. In that time he examined black recruits at Benedict and Baltimore, Maryland. Yet racism followed him. For example, the army paymaster initially paid him at the same rate that was provided for enlisted men after their clothing deduction: $7 a month. However, Senator Henry Wilson of Massachusetts heard Augusta’s complaint, wrote to the secretary of war about the matter, and two days later the paymaster general was ordered to compensate the surgeon according to his rank.

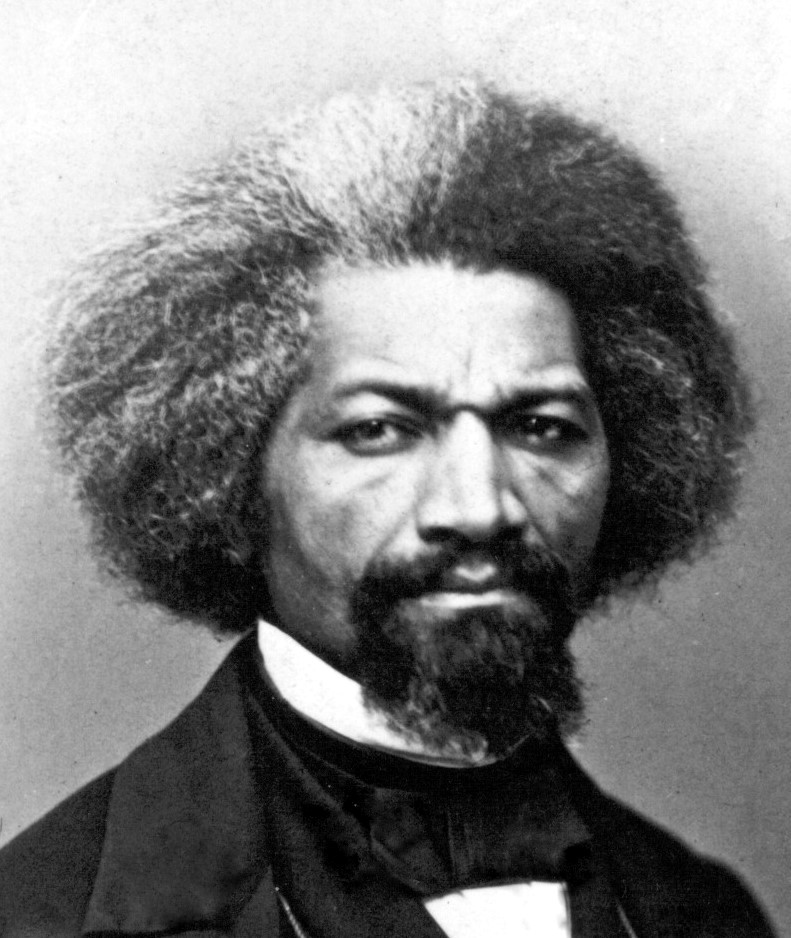

In 1865 and 1866, Augusta was assigned to the Department of the South. For his meritorious service, in March 1865 he was promoted to lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Volunteers, becoming the first black to hold that rank. While on a lengthy tour of duty, he headed a hospital in Savannah, Georgia. Many black casualties of the Civil War resulted from the hesitancy of the U.S. Army to arm these soldiers in the first place. The excessive casualty rate of the colored troops was also due to the lack of medical care that they received. White surgeons resisted serving with black troops and were reluctant to treat ailing black soldiers. Of the eight black physicians who were appointed surgeons in the army, seven were attached to hospitals in the Washington, D.C. area. These included Charles B. Purvis and John Rapier. John V. De Grasse had only a brief stint with the 35th U.S. Colored Infantry, as assistant surgeon. In The History of the Negro in Medicine, Herbert M. Morais writes: “Of this small band of doctors in blue, the most illustrious was Alexander T. Augusta.” Augusta mustered out of service on October 13, 1866, and returned to Washington, D.C, where he opened private practice.

In 1865 and 1866, Augusta was assigned to the Department of the South. For his meritorious service, in March 1865 he was promoted to lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Volunteers, becoming the first black to hold that rank. While on a lengthy tour of duty, he headed a hospital in Savannah, Georgia. Many black casualties of the Civil War resulted from the hesitancy of the U.S. Army to arm these soldiers in the first place. The excessive casualty rate of the colored troops was also due to the lack of medical care that they received. White surgeons resisted serving with black troops and were reluctant to treat ailing black soldiers. Of the eight black physicians who were appointed surgeons in the army, seven were attached to hospitals in the Washington, D.C. area. These included Charles B. Purvis and John Rapier. John V. De Grasse had only a brief stint with the 35th U.S. Colored Infantry, as assistant surgeon. In The History of the Negro in Medicine, Herbert M. Morais writes: “Of this small band of doctors in blue, the most illustrious was Alexander T. Augusta.” Augusta mustered out of service on October 13, 1866, and returned to Washington, D.C, where he opened private practice.

Augusta’s prominence in the field of medicine was acknowledged in 1868, when the newly organized Medical Department at Howard University elected him demonstrator of anatomy, making him the first black to be offered a teaching position at any medical school in the United States. In what was called the Panic of 1893, a time of severe financial difficulties at the medical school, the medical faculty faced the dilemma of resigning or having their salaries cut in half. Some resigned, but Augusta, Purvis, and Gideon Stimson Palmer remained. Augusta continued on the faculty until September 14, 1877, holding a succession of professorships in anatomy while serving on the staff of Freedmen’s Hospital. The school reorganized and wanted to move Augusta from the head of the Anatomy Department to chair of Materia Medica. Augusta declined the new appointment and was terminated. He reentered private practice in 1877.

Honors Come Slowly

On June 9, 1879, Augusta and Purvis were proposed for membership in the Medical Society of the District of Columbia, an affiliate of the American Medical Association. On June 23, Dr. A. W. Tucker’s name was added to the list. All of the men were rejected. On February 8, 1870, Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts introduced a bill in the U.S. Senate to repeal the charter of the Medical Society of the District of Columbia because it worked against black practitioners and was guilty of discriminatory practices. The bill was unsuccessful, and the fight continued. Blacks, however, on January 15, 1870, formed their own National Medical Society of the District of Columbia and accepted whites into membership. The fight to integrate the local white medical society continued for many years; eventually the local society revised its regulations and allowed consultations with black physicians.

Howard University recognized its star medical school faculty on June 27, 1871, when it awarded honorary M.A. degrees to Augusta, Purvis, and Robert Reyburn. Augusta also received an honorary degree of Medicinal Doctor on June 30, 1896. In honor of the noted surgeon and educator, in 1913 doctors Simeon L. Carson, B. Price Hurst, Peter M. Murray, and E. A. Robinson formed the Alexander T. Augusta Medical Reading Club; it grew to a maximum of twelve but ceased to exist around 1940 due to the deaths of several members.

Howard University recognized its star medical school faculty on June 27, 1871, when it awarded honorary M.A. degrees to Augusta, Purvis, and Robert Reyburn. Augusta also received an honorary degree of Medicinal Doctor on June 30, 1896. In honor of the noted surgeon and educator, in 1913 doctors Simeon L. Carson, B. Price Hurst, Peter M. Murray, and E. A. Robinson formed the Alexander T. Augusta Medical Reading Club; it grew to a maximum of twelve but ceased to exist around 1940 due to the deaths of several members.

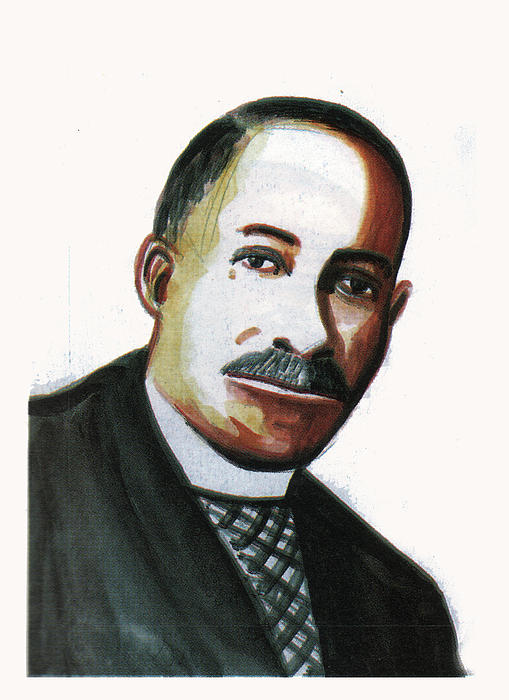

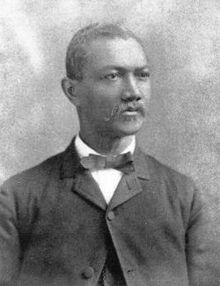

Augusta, a quiet, slender, and handsome man, died at his home, 1319 L Street, NW, Washington, D.C., on December 21, 1890. After the funeral at St. John’s Episcopal Church at Lafayette Square, held on December 24, his body was buried in Arlington National Cemetery. Augusta is remembered as a pioneer black surgeon, medical school professor, and practicing physician who persevered against odds early on and obtained a medical school degree and broke racial barriers in the military, in hospital administration, and in medical education.