"The blood of individual human beings may differ by blood groupings, but there is absolutely no scientific basis to indicate any difference in human blood from race to race."

-Charles Richard Drew

I can remember how shocked I was when I found out about this next notable figure. I'd thought that the creator of the blood banks was a white man and to find out that it was in fact a black man was amazing to me, especially when that man's own blood would be segregated because of a ruling during his time.

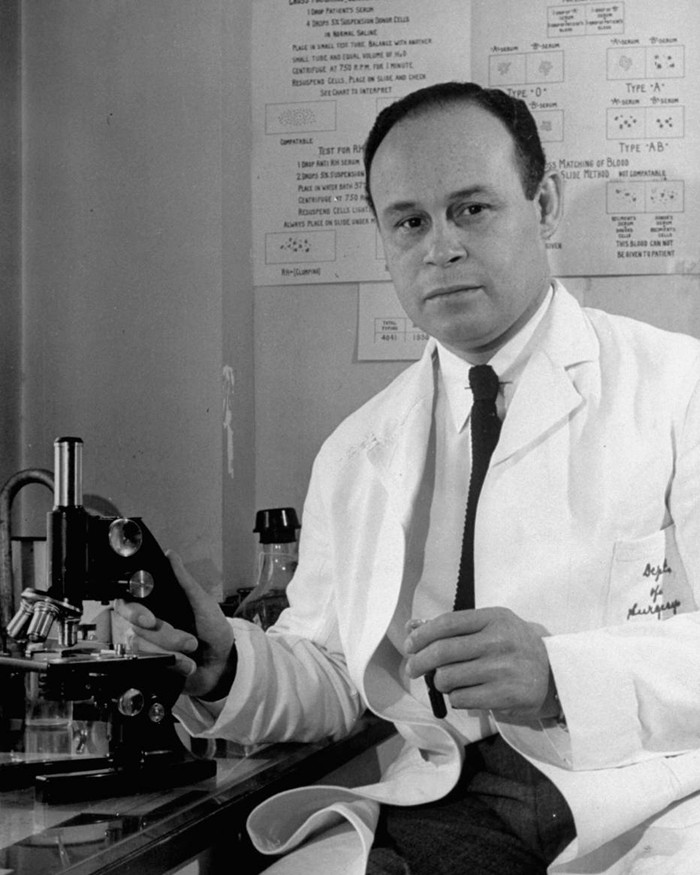

This is the amazing story of African-American physician, Dr. Charles Drew.

****

Charles Richard Drew was born on June 3, 1904, in Washington, D.C. He was an African-American physician who developed ways to process and store blood plasma in "blood banks." He directed the blood plasma programs of the United States and Great Britain in World War II, but resigned after a ruling that the blood of African-Americans would be segregated. He died in 1950.

A pioneering African-American medical researcher, Dr. Charles R. Drew made some groundbreaking discoveries in the storage and processing of blood for transfusions. He also managed two of the largest blood banks during World War II. Drew grew up in Washington, D.C., as the oldest son of a carpet layer.

In his youth, Drew showed great athletic talent. He won several medals for swimming in his elementary years, and later branched out to football, basketball and other sports. After graduating from Dunbar High School in 1922, Drew went to Amherst College on a sports scholarship. There, he distinguished himself on the track and football teams.

In his youth, Drew showed great athletic talent. He won several medals for swimming in his elementary years, and later branched out to football, basketball and other sports. After graduating from Dunbar High School in 1922, Drew went to Amherst College on a sports scholarship. There, he distinguished himself on the track and football teams.Drew completed his bachelor's degree at Amherst in 1926, but didn't have enough money to pursue his dream of attending medical school. He worked as a biology instructor and a coach for Morgan College, now Morgan State University, in Baltimore for two years. In 1928, he applied to medical schools and enrolled at McGill University in Montreal, Canada.

At McGill University, Drew quickly proved to be a top student. He won a prize in neuroanatomy and was a member of the Alpha Omega Alpha, a medical honor society. Graduating in 1933, Drew was second in his class and earned both Doctor of Medicine and Master of Surgery degrees. He did his internship and residency at the Royal Victoria Hospital and the Montreal General Hospital. During this time, Drew studied with Dr. John Beattie, and they examined problems and issues regarding blood transfusions.

After his father's death, Drew returned to the United States. He became an instructor at Howard University's medical school in 1935. The following year, he did a surgery residence at Freedmen's Hospital in Washington, D.C., in addition to his work at the university.

Father of Blood Banks

In 1938, Drew received a Rockefeller Fellowship to study at Columbia University and train at the Presbyterian Hospital in New York City. There, he continued his exploration of blood-related matters with John Scudder. Drew developed a method for processing and preserving blood plasma, or blood without cells. Plasma lasts much longer than whole blood, making it possible to be stored or "banked" for longer periods of time. He discovered that the plasma could be dried and then reconstituted when needed. His research served as the basis of his doctorate thesis, "Banked Blood," and he received his doctorate degree in 1940. Drew became the first African-American to earn this degree from Columbia.

As World War II raged in Europe, Drew was asked to head up a special medical effort known as "Blood for Britain." He organized the collection and processing of blood plasma from several New York hospitals, and the shipments of these life-saving materials overseas to treat causalities in the war.

According to one report, Drew helped collect roughly 14,500 pints of plasma.

According to one report, Drew helped collect roughly 14,500 pints of plasma.In 1941, Drew worked on another blood bank effort, this time for the American Red Cross. He worked on developing a blood bank to be used for U.S. military personnel. But not long into his tenure there, Drew became frustrated with the military's request for segregating the blood donated by African-Americans. At first, the military did not want to use blood from African-Americans, but they later said it could only be used for African-American soldiers. Drew was outraged by this racist policy, and resigned his post after only a few months.

Death and Legacy

After creating two of the first blood banks, Drew returned to Howard University in 1941. He served as a professor there, heading up the university's department of surgery. He also became the chief surgeon at Freedmen's Hospital. Later that year, he became the first African-American examiner for the American Board of Surgery.

In 1944, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People honored Drew with its 1943 Spingarn Medal for "the highest and noblest achievement" by an African-American "during the preceding year or years." The award was given in recognition of Drew's blood plasma collection and distribution efforts.

For the final years of his life, Drew remained an active and highly regarded medical professional. He continued to serve as the chief surgeon at Freedmen's Hospital and a professor at Howard University. On April 1, 1950, Drew and three other physicians attended a medical conference at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. Drew was behind the wheel when his vehicle crashed near Burlington, North Carolina. His passengers survived, but Drew later succumbed to his injuries. He left behind his wife, Minnie, and their four children.

Drew was only 45 years old at the time of his death, and it is remarkable how much he was able to accomplish in such a limited amount of time. As the Reverend Jerry Moore said at Drew's funeral, Drew had "a life which crowds into a handful of years' significance, so great, men will never be able to forget it."

Since his passing, Drew has received countless posthumous honors. He was featured in the United States Postal Service's Great Americans stamp series in 1981, and his name appears on educational institutions across the country.

(*Charles Richard Drew. (2014). The Biography Channel website. Retrieved 07:54, Feb 09, 2014, from http://www.biography.com/people/charles-drew-9279094.*)

Charles Drew was born on June 3, 1904 in Washington, D.C., the son of Richard and Nora Drew and eldest of five children. Charles was one of those rare individuals who seemed to excel at everything he did and on every level and would go on to become of pioneer in the field of medicine.

Charles' early interests were in education, particularly in medicine, but he was also an outstanding athlete. As a youngster he was an award winning swimmer and starred Dunbar High School in football, baseball, basketball and track and field, winning the James E. Walker Memorial medal as his school's best all around athlete. After graduation from Dunbar in 1922, he went on to attend Amherst College in Massachusetts where he captained the track team and starred as a halfback on the school's football team, winning the Thomas W. Ashley Memorial trophy in his junior year as the team most valuable player and being named to the All-American team. Drew had a rich assortment of graduation announcements and convocations since his education was extensive through his life. Upon graduation from Amherst in 1926 he was awarded the Howard Hill Mossman trophy as the man who contributed the most to Amherst athletics during his four years in school.

After graduation from Amherst, Drew took on a position as a biology teacher at Morgan State University in Baltimore, Maryland and also served as the school's Athletic Director. During his two years at Morgan State, he helped to turn the school's basketball and football programs into collegiate champions.

In 1928, Charles decided to pursue his interest in medicine and enrolled at McGill University in Montreal, Canada. He was received as a member of the Medical Honorary Society and graduated in 1933 with Master of Surgery and Doctor of Medicine degrees, finishing second in his class of 127 students. He stayed in Montreal for a while as an intern at Montreal General Hospital and at the Royal Victoria Hospital. In 1935, he returned to the United States and began working as an instructor of pathology at Howard University in Washington, D.C. He was also a resident at Freedmen's Hospital (the teaching hospital for Howard University) and was awarded the Rockefeller Foundation Research Fellowship.

He spent two years at Columbia University in New York attending classes and working as a resident at the Columbia University Presbyterian Hospital. During this time he became involved in research on blood and blood transfusions.

Years back, while a student at McGill, he had saved a man by giving him a blood transfusion and had studied under Dr. John Beattie, an instructor of anatomy who was intensely interested in blood transfusions. Now at Columbia, he wrote a dissertation on "Banked Blood" in which he described a technique he developed for the long-term preservation of blood plasma. Prior to his discovery, blood could not be stored for more than two days because of the rapid breakdown of red blood cells. Drew had discovered that by separating the plasma (the liquid part of blood) from the whole blood (in which the red blood cells exist) and then refrigerating them separately, they could be combined up to a week later for a blood transfusion. He also discovered that while everyone has a certain type of blood (A, B, AB, or O) and thus are prevented from receiving a full blood transfusion from someone with different blood, everyone has the same type of plasma. Thus, in certain cases where a whole blood transfusion is not necessary, it was sufficient to give a plasma transfusion which could be administered to anyone, regardless of their blood type. He convinced Columbia University to establish a blood bank and soon was asked to go to England to help set up that country's first blood bank. Drew became the first Black to receive a Doctor of Medical Science degree from Columbia and was now gaining a reputation worldwide.

On September 29, 1939, Charles married Lenore Robbins, with whom he would have four children. At the same time, however, World War II was breaking out in Europe. Drew was named the Supervisor of the Blood Transfusion Association for New York City and oversaw its efforts towards providing plasma to the British Blood Bank. He was later named a project director for the American Red Cross but soon resigned his post after the United States War Department issued a directive that blood taken from White donors should be segregated from that of Black donors.

On September 29, 1939, Charles married Lenore Robbins, with whom he would have four children. At the same time, however, World War II was breaking out in Europe. Drew was named the Supervisor of the Blood Transfusion Association for New York City and oversaw its efforts towards providing plasma to the British Blood Bank. He was later named a project director for the American Red Cross but soon resigned his post after the United States War Department issued a directive that blood taken from White donors should be segregated from that of Black donors.Dr. Charles Drew attending to a patient.In 1942, Drew returned to Howard University to head its Department of Surgery, as well as the Chief of Surgery at Freedmen's Hospital. Later he was named Chief of Staff and Medical Director for the Hospital. In 1948 he was awarded the Spingarn Medal from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People for his work on blood plasma. He was also presented with the E. S. Jones Award for Research in Medical Science and became the first Black to be appointed an examiner by the American Board of Surgery. In 1945 he was presented honorary degrees of Doctor of Science from Virginia State College as well as Amherst College where he attended as an undergraduate student. In 1946 he was elected Fellow of the International College of Surgeons and in 1949 appointed Surgical Consultant for the United States Army's European Theater of Operations.

Dr. Charles Drew died on April 1, 1950 when the automobile he was driving went out of control and turned over. Drew suffered extensive massive injuries but contrary to popular legend was not denied a blood transfusion by an all-White hospital - he indeed received a transfusion but was beyond the help of the experienced physicians attending to him. His family later wrote letters to those physicians thanking them for the care they provided. Over the years, Drew has been considered one of the most honored and respected figures in the medical field and his development of the blood plasma bank has given a second chance of live to millions.

(*http://www.blackinventor.com/pages/charles-drew.html*)

Amazing! So much accomplished and so short a life. I had no idea who was behind storage of plasma. Such talent!

ReplyDeleteTj