They told us we wouldn’t get here. And there were those who said that we would get here only over their dead bodies, but all the world today knows that we are here and we are standing before the forces of power in the state of Alabama saying, "We ain’t goin’ let nobody turn us around."

-Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. "Address at the Conclusion of the Selma to Montgomery March"

When I first learned about "Bloody Sunday" and the Selma to Montgomery Marches I was 10 years old, just finding out about my black heritage and being overwhelmed with images of slavery, the Civil War, Jim Crow, and the Civil Rights Movement. I was horrified by the videos and the photos but encouraged and uplifted when I realized that no matter how much oppression and violence they suffered these people, these fighters for justice, these nonviolent protesters for civil rights, never gave up. They marched on. They kept singing. And they kept pushing forward towards justice.

While "Bloody Sunday" was heart-wrenching, the march that followed it was one of triumph.

Join with me in honoring those who marched, were attacked, and yet returned to march again from Selma to Montgomery.

****

On 2 January 1965 King and SCLC joined the SNCC, the Dallas County Voters League, and other local African American activists in a voting rights campaign in Selma where, in spite of repeated registration attempts by local blacks, only two percent were on the voting rolls. SCLC had chosen to focus its efforts in Selma because they anticipated that the notorious brutality of local law enforcement under Sheriff Jim Clark would attract national attention and pressure President Lyndon B. Johnson and Congress to enact new national voting rights legislation.

Now it is not an accident that one of the great marches of American history should terminate in Montgomery, Alabama. Just ten years ago, in this very city, a new philosophy was born of the Negro struggle. Montgomery was the first city in the South in which the entire Negro community united and squarely faced its age-old oppressors. Out of this struggle, more than bus [de]segregation was won; a new idea, more powerful than guns or clubs was born. Negroes took it and carried it across the South in epic battles that electrified the nation and the world.

-Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. "Address at the Conclusion of the Selma to Montgomery Marches"

The campaign in Selma and nearby Marion, Alabama, progressed with mass arrests but little violence for the first month. That changed in February, however, when police attacks against nonviolent demonstrators increased. On the night of 18 February, Alabama state troopers joined local police breaking up an evening march in Marion. In the ensuing melee, a state trooper shot Jimmie Lee Jackson, a 26-year-old church deacon from Marion, as he attempted to protect his mother from the trooper’s nightstick. Jackson died eight days later in a Selma hospital.

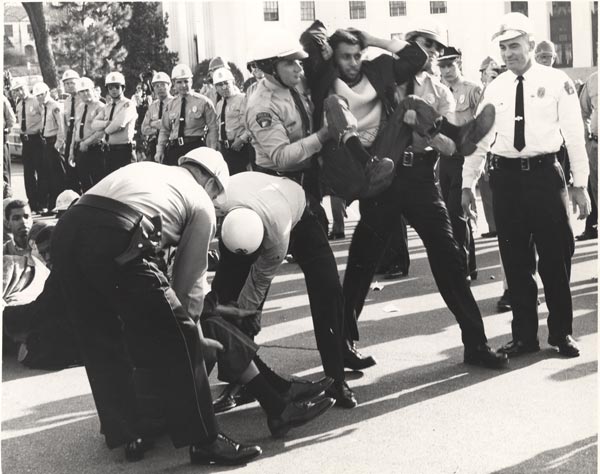

In response to Jackson’s death, activists in Selma and Marion set out on 7 March, to march from Selma to the state capitol in Montgomery. While King was in Atlanta, his SCLC colleague Hosea Williams, and SNCC leader John Lewis led the march. The marchers made their way through Selma across the Edmund Pettus Bridge, where they faced a blockade of state troopers and local lawmen commanded by Clark and Major John Cloud who ordered the marchers to disperse. When they did not, Cloud ordered his men to advance. Cheered on by white onlookers, the troopers attacked the crowd with clubs and tear gas. Mounted police chased retreating marchers and continued to beat them.

In response to Jackson’s death, activists in Selma and Marion set out on 7 March, to march from Selma to the state capitol in Montgomery. While King was in Atlanta, his SCLC colleague Hosea Williams, and SNCC leader John Lewis led the march. The marchers made their way through Selma across the Edmund Pettus Bridge, where they faced a blockade of state troopers and local lawmen commanded by Clark and Major John Cloud who ordered the marchers to disperse. When they did not, Cloud ordered his men to advance. Cheered on by white onlookers, the troopers attacked the crowd with clubs and tear gas. Mounted police chased retreating marchers and continued to beat them. Television coverage of ‘‘Bloody Sunday,’’ as the event became known, triggered national outrage. Lewis, who was severely beaten on the head, said: ‘‘I don’t see how President Johnson can send troops to Vietnam—I don’t see how he can send troops to the Congo—I don’t see how he can send troops to Africa and can’t send troops to Selma,’’ (Reed, ‘‘Alabama Police Use Gas’’).

Television coverage of ‘‘Bloody Sunday,’’ as the event became known, triggered national outrage. Lewis, who was severely beaten on the head, said: ‘‘I don’t see how President Johnson can send troops to Vietnam—I don’t see how he can send troops to the Congo—I don’t see how he can send troops to Africa and can’t send troops to Selma,’’ (Reed, ‘‘Alabama Police Use Gas’’).

On our part we must pay our profound respects to the white Americans who cherish their democratic traditions over the ugly customs and privileges of generations and come forth boldly to join hands with us. From Montgomery to Birmingham, (Yes, sir) from Birmingham to Selma, from Selma back to Montgomery, a trail wound in a circle long and often bloody, yet it has become a highway up from darkness. Alabama has tried to nurture and defend evil, but evil is choking to death in the dusty roads and streets of this state. So I stand before you this afternoon with the conviction that segregation is on its deathbed in Alabama, and the only thing uncertain about it is how costly the segregationists and Wallace will make the funeral.

-Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. "Address at the Conclusion of the Selma to Montgomery Marches"

That evening King began a blitz of telegrams and public statements, ‘‘calling on religious leaders from all over the nation to join us on Tuesday in our peaceful, nonviolent march for freedom’’ (King, 7 March 1965). While King and Selma activists made plans to retry the march again two days later, Federal District Court Judge Frank M. Johnson, Jr. notified the movement attorney Fred Gray that he intended to issue a restraining order prohibiting the march until at least 11 March, and President Johnson pressured King to call off the march until the federal court order could provide protection to the marchers.

Forced to consider whether to disobey the pending court order, after consulting late into the night and early morning with other civil rights leaders and John Doar, the deputy chief of the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division, King proceeded to the Edmund Pettus Bridge on the afternoon of 9 March. He led more than 2,000 marchers, including hundreds of clergy who had answered King’s call on short notice, to the site of Sunday’s attack, then stopped and asked them to kneel and pray. After prayers they rose and turned the march back to Selma, avoiding another confrontation with state troopers and skirting the issue of whether to obey Judge Johnson’s court order. Many marchers were critical of King’s unexpected decision not to push on to Montgomery, but the restraint gained support from President Johnson, who issued a public statement: ‘‘Americans everywhere join in deploring the brutality with which a number of Negro citizens of Alabama were treated when they sought to dramatize their deep and sincere interest in attaining the precious right to vote’’ (Johnson, ‘‘Statement by the President,’’ 272). Johnson promised to introduce a voting rights bill to Congress within a few days.

Forced to consider whether to disobey the pending court order, after consulting late into the night and early morning with other civil rights leaders and John Doar, the deputy chief of the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division, King proceeded to the Edmund Pettus Bridge on the afternoon of 9 March. He led more than 2,000 marchers, including hundreds of clergy who had answered King’s call on short notice, to the site of Sunday’s attack, then stopped and asked them to kneel and pray. After prayers they rose and turned the march back to Selma, avoiding another confrontation with state troopers and skirting the issue of whether to obey Judge Johnson’s court order. Many marchers were critical of King’s unexpected decision not to push on to Montgomery, but the restraint gained support from President Johnson, who issued a public statement: ‘‘Americans everywhere join in deploring the brutality with which a number of Negro citizens of Alabama were treated when they sought to dramatize their deep and sincere interest in attaining the precious right to vote’’ (Johnson, ‘‘Statement by the President,’’ 272). Johnson promised to introduce a voting rights bill to Congress within a few days.That evening, several local whites attacked James Reeb, a white Unitarian minister who had come from Massachusetts to join the protest. His death two days later contributed to the rising national concern over the situation in Alabama. Johnson personally telephoned his condolences to Reeb’s widow and met with Alabama Governor George Wallace, pressuring him to protect marchers and support universal suffrage.

On 15 March Johnson addressed the Congress, identifying himself with the demonstrators in Selma in a televised address: ‘‘Their cause must be our cause too. Because it is not just Negroes, but really it is all of us, who must overcome the crippling legacy of bigotry and injustice. And we shall overcome’’ (Johnson, ‘‘Special Message’’). The following day Selma demonstrators submitted a detailed march plan to federal Judge Frank M. Johnson, Jr., who approved the demonstration and enjoined Governor Wallace and local law enforcement from harassing or threatening marchers. On 17 March President Johnson submitted voting rights legislation to Congress.

On 15 March Johnson addressed the Congress, identifying himself with the demonstrators in Selma in a televised address: ‘‘Their cause must be our cause too. Because it is not just Negroes, but really it is all of us, who must overcome the crippling legacy of bigotry and injustice. And we shall overcome’’ (Johnson, ‘‘Special Message’’). The following day Selma demonstrators submitted a detailed march plan to federal Judge Frank M. Johnson, Jr., who approved the demonstration and enjoined Governor Wallace and local law enforcement from harassing or threatening marchers. On 17 March President Johnson submitted voting rights legislation to Congress.The federally sanctioned march left Selma on 21 March. Protected by hundreds of federalized Alabama National Guardsmen and Federal Bureau of Investigation agents, the demonstrators covered between 7 to 17 miles per day. Camping at night in supporters’ yards, they were entertained by celebrities such as Harry Belafonte and Lena Horne. Limited by Judge Johnson’s order to 300 marchers over a stretch of two-lane highway, the number of demonstrators swelled on the last day to 25,000, accompanied by Assistant Attorneys General John Doar and Ramsey Clark, and former Assistant Attorney General Burke Marshall, among others.

Today I want to tell the city of Selma, today I want to say to the state of Alabama, today I want to say to the people of America and the nations of the world, that we are not about to turn around. We are on the move now.

Yes, we are on the move and no wave of racism can stop us. We are on the move now. The burning of our churches will not deter us. The bombing of our homes will not dissuade us. We are on the move now. The beating and killing of our clergymen and young people will not divert us. We are on the move now. The wanton release of their known murderers would not discourage us. We are on the move now. Like an idea whose time has come, not even the marching of mighty armies can halt us. We are moving to the land of freedom.

-Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. "Address at the Conclusion of the Selma to Montgomery Marches"

During the final rally, held on the steps of the capitol in Montgomery, King proclaimed: ‘‘The end we seek is a society at peace with itself, a society that can live with its conscience. And that will be a day not of the white man, not of the black man. That will be the day of man as man’’ (King, ‘‘Address,’’ 130). Afterward a delegation of march leaders attempted to deliver a petition to Governor Wallace, but were rebuffed. That night, while ferrying Selma demonstrators back home from Montgomery, Viola Liuzzo, a housewife from Michigan who had come to Alabama to volunteer, was shot and killed by four members of the Ku Klux Klan. Doar later prosecuted three Klansmen conspiring to violate her civil rights.

On 6 August, in the presence of King and other civil rights leaders, President Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Recalling ‘‘the outrage of Selma,’’ Johnson

called the right to vote ‘‘the most powerful instrument ever devised by man for breaking down injustice and destroying the terrible walls which imprison men because they are different from other men’’ (Johnson, ‘‘Remarks’’). In his annual address to SCLC a few days later, King noted that ‘‘Montgomery led to the Civil Rights Act of 1957 and 1960; Birmingham inspired the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and Selma produced the voting rights legislation of 1965’’ (King, 11 August 1965).

I know you are asking today, "How long will it take?" Somebody’s asking, "How long will prejudice blind the visions of men, darken their understanding, and drive bright-eyed wisdom from her sacred throne?" Somebody’s asking, "When will wounded justice, lying prostrate on the streets of Selma and Birmingham and communities all over the South, be lifted from this dust of shame to reign supreme among the children of men?" Somebody’s asking, "When will the radiant star of hope be plunged against the nocturnal bosom of this lonely night, plucked from weary souls with chains of fear and the manacles of death? How long will justice be crucified, and truth bear it?"

I come to say to you this afternoon, however difficult the moment, however frustrating the hour, it will not be long, because "truth crushed to earth will rise again."

-Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr "Address at the Conclusion of the Selma to Montgomery Marches

SOURCES

Garrow, Protest at Selma, 1978.

Johnson, ‘‘Remarks in the Capitol Rotunda at the Signing of the Voting Rights Act,’’ 6 August 1966, in Public Papers of the Presidents: Lyndon B. Johnson, 1965, bk.2, 1966.

Johnson, ‘‘Special Remarks to the Congress: The American Promise,’’ 15 March 1965, in Public Papers of the Presidents: Lyndon B. Johnson, bk. 1, 1966.

Johnson, ‘‘Statement by the President on the Situation in Selma, Alabama,’’ 9 March 1965, in Public Papers of the Presidents: Lyndon B. Johnson, 1965, bk. 1, 1966.

King, ‘‘Address at Conclusion of the Selma to Montgomery March,’’ in A Call to Conscience, Carson and Shepard, eds., 2001.

King, Annual report at SCLC convention, 11 August 1965, MLKJP-GAMK.

King, Statement on violence committed by state troopers in Selma, Alabama, 7 March 1965, MLKJP-GAMK.

King to Elder G. Hawkins, 8 March 1965, NCCP-PPPrHi.

Lewis, Walking with the Wind, 1998.

Roy Reed, ‘‘Alabama Police Use Gas and Clubs to Rout Negroes,’’ New York Times, 8 March 1965.

(*http://mlk-kpp01.stanford.edu/index.php/encyclopedia/encyclopedia/enc_selma_to_montgomery_march/*)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Want to pet The Vic?